Ticks and Lyme Disease in Scotland: A Growing Public Health Concern

Increasing numbers of tick, an expanding range, and more hosts are creating the perfect storm for a growing and often overlooked public health concern.

Ticks are found throughout Scotland, and their numbers and range are on the rise. A combination of milder winters, warmer and wetter conditions, and a growing abundance of suitable hosts, means ticks can survive for longer periods and spread into new environments, including places where they have been historically absent. Traditionally associated with rural areas, particularly upland landscapes, ticks are now being reported more frequently in peri-urban environments, such as parks, gardens, and woodland edges close to towns and villages, demonstrating a concerning trend.

Ticks key hosts include deer, rodents, birds, and livestock such as sheep. Red and roe deer are particularly important for adult ticks, providing the large blood meals needed for reproduction, while smaller mammals like mice and voles play a critical role in feeding larvae and nymphs. Together, these animals sustain and disperse tick populations throughout a wide range of habitats.

Woodland and upland regions, including montane habitats that were previously too cold to support ticks, are seeing a rise in tick activity. Their active season, once limited to spring and summer, is now stretching well into the autumn, and in some regions, tick activity is being recorded year round. For those of us who live and work in the countryside, this comes as no surprise, as the presence of ticks now forms part of our daily lives.

Worryingly, this trend only looks set to continue in the face of climate change, as demonstrated in a recent study by the University of Stirling. Climate modelling was used to examine the future of tick populations under global warming scenarios, the findings of which suggest that tick numbers in Scotland could increase by 26% with a 1°C rise in temperature, and could nearly double with a 4°C rise by 2080.

But why does an increase in tick numbers and range matter?

Lyme Disease

Some ticks (mainly carried by the sheep or deer tick Ixodes ricinus) carry Lyme disease, a bacterial infection which can be transmitted to humans through a bite from an infected tick. Early symptoms include a characteristic ‘bull's-eye’ rash, fever, and fatigue, but if left untreated, can spread to the joints, the heart, and the nervous system, leading to serious and prolonged health issues.

Lyme disease is often difficult to diagnose because its symptoms are non-specific and can easily be confused with other conditions. While some people develop the telltale bull’s-eye rash, equally many do not, and early blood tests can miss the infection if antibodies haven’t developed yet. In Scotland, as in much of the UK, there is a lack of dedicated research and limited clinical awareness, which can lead to misdiagnosis or delays in treatment.

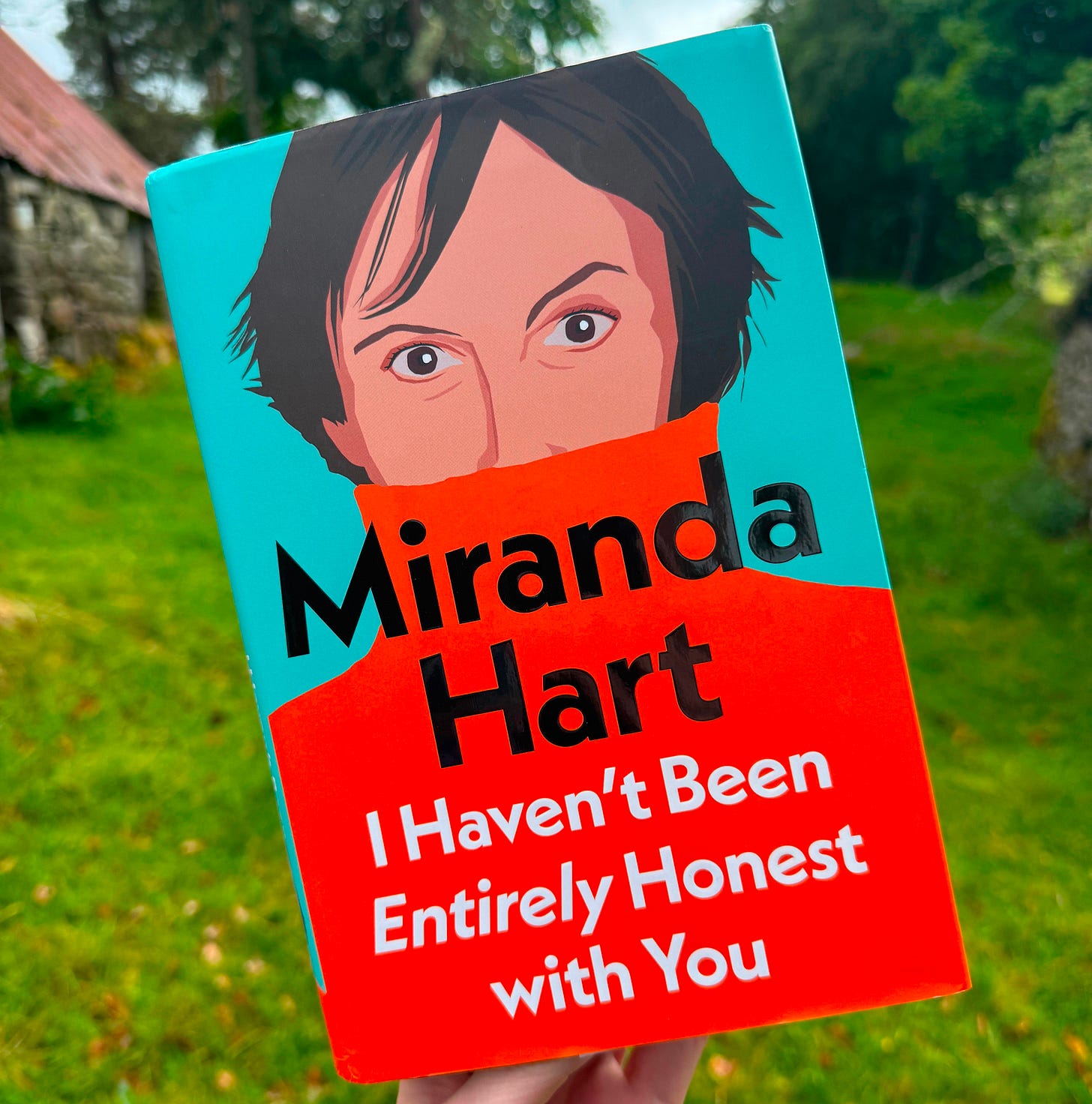

High-profile cases have brought much needed attention to the challenges of diagnosing and treating Lyme disease. Most recently, British comedian Miranda Hart detailed her decade-long struggle with undiagnosed Lyme disease in her memoir I Haven't Been Entirely Honest With You. Left exhausted and housebound for years, she was continuously misdiagnosed and misunderstood, highlighting the complexities of chronic illness and the importance of awareness and early detection.

It is understood Scotland already has some of the highest Lyme disease rates in the UK, but as it is not a notifiable disease, the true number of new cases per year is unknown. Whilst awareness is increasing, Lyme disease remains under-recognised, under-reported, and poorly understood.

The Role of Wild Deer

In many parts of the country, especially in the Highlands, deer populations have increased substantially in recent decades. More deer mean more feeding opportunities for ticks, which in turn boosts their survival and reproduction rates. Deer also act as carriers, moving ticks across large areas and helping them reach new habitats.

However, before blame is fully attributed to deer, it is important to note that while they support large tick populations due to their size and abundance, deer do not transmit the Borrelia bacteria that cause Lyme disease. This makes them what scientists refer to as ‘non-competent hosts’. Although rising deer numbers lead to more ticks in the environment, this does not directly increase the number of infected ticks. In fact, it may even reduce infection rates through a ‘dilution effect’, where the number of uninfected ticks increases faster than those carrying the bacteria.

Still, while the relationship between deer density and Lyme disease risk is not straightforward, further action has been recognised as being necessary. In 2017, the Scottish Government commissioned the Deer Working Group to review and recommend improvements to the management of wild deer in Scotland. The group's report, published in February 2020, includes 99 recommendations aimed at ensuring sustainable deer management that safeguards public interests and promotes ecological balance. One of those recommendations relates specifically to Lyme disease:

‘The Working Group recommends that the Scottish Government should ensure that the role of wild deer in increasing the risk of Lyme disease is given greater prominence in its policies for deer management in Scotland, and that greater priority is given to that risk in considering the need to reduce deer densities in locations across Scotland.’

Although this recommendation has not been directly implemented as yet, research is underway to explore innovative strategies for controlling tick populations on deer. These include the potential use of acaricides (chemicals that kill ticks), and GPS tracking to monitor deer movements, helping scientists understand how ticks spread between habitats. While the use of acaricides on wild deer remains largely theoretical, ongoing research into deer ecology continues to inform more practical, integrated approaches to tick management.

The Role of Sheep

In many areas of Scotland, sheep are routinely treated with acaricides. These treatments principally protect the animals themselves but are also used as a wider strategy to manage tick populations on predominantly hill ground. This approach is particularly important in areas where tick-borne diseases like louping ill are a threat. Louping ill is a viral disease primarily affecting sheep and occasionally other animals such as red grouse and goats. It is spread by the same species of tick responsible for transmitting Lyme disease.

By treating sheep with acaricides through dips, sprays, or pour-ons, the aim is to prevent tick bites and reduce the risk of viral transmission. This method also turns treated sheep into what’s known as a ‘tick mop’, meaning as sheep move through infested habitats, ticks that attach to them are killed by the chemical treatment, reducing the number of ticks in the environment overall. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the frequency and consistency of treatment, and while it’s a valuable part of moorland management, it has raised concerns about environmental impacts and the risk of acaricide resistance developing over time.

Raising Awareness

Over the past decade, charities like Lyme Disease UK have played a vital role in raising awareness about tick-borne health risks and advocating for better diagnosis, treatment, and recognition of Lyme disease. Their work includes public campaigns, online resources, patient support, and lobbying for increased research and policy improvements. They also collaborate with medical professionals to improve understanding and promote earlier diagnosis.

Information and advice on how to protect yourself is now much more prevalent and includes things like wearing long sleeve tops and tucking trousers into socks, using a suitable repellent and avoiding tall grass. Employers also have an important role in protecting employees, by providing training, information, and protective equipment where necessary.

There are guides on how to check yourself and others for ticks, how to safely remove them and what to do if you feel unwell following a bite. The advice also includes checking your pets regularly and removing any ticks, be they attached or otherwise. Dogs in particular can pick up ticks very easily and increase the chance of exposure to their owners. Spot-on treatments are available to help kill ticks and are effective if used regularly but are unlikely to stop transmission.

Interestingly, the most effective method I have found to prevent ticks from being transmitted into the house and car is something that is inexpensive, widely accessible, portable, and convenient to use at any time: a lint roller. Although it may require several sheets to complete the task, it has proven to be a simple and highly effective measure, especially when used on dogs.

What next?

As tick populations spread and Lyme disease cases continue to rise, this is becoming an increasingly important public health concern in Scotland. What was once seen as a rural, and somewhat seasonal problem, is now affecting more people in more places. Yet, despite the growing risk, public awareness remains a challenge, with the condition still under-recognised by many in the healthcare system. Difficulties in diagnosis, limited reporting, and inconsistent treatment approaches only add to the burden faced by those affected.

While ongoing research and awareness campaigns are helping to close the gap, there is a pressing need for better surveillance, clearer clinical guidelines, and more education for both the public and medical professionals.

Tackling ticks and Lyme disease must now be seen not just as a rural challenge, but as a public health concern, and one which requires coordinated, long-term action to protect communities across Scotland.

Thank you for an informative post. Lymes disease is a horrible thing and there really should be more research into it.

Since we moved to Scotland from the south of England, we have become more observant. But, as you say, ticks are widespread across the UK so there's no escaping them.

Interested in your tip: how/when do you use the lint roller?

Really appreciated this practical and personal piece, especially the reminder that awareness can be life-changing. I’ve started carrying a tick remover in every coat pocket and back since a close call.

It’s such a tricky balance, though. Acaricides can seem like a quick fix, but they don’t just target ticks, they also harm beneficial arthropods like spiders, predatory mites, and insects that keep ecosystems ticking along through soil health, pollination, and natural pest control. And overuse can lead to resistance in tick populations, making the problem worse long-term.

I think ticks feel like a symptom of something deeper - an ecosystem out of whack. Thank you for opening up this conversation. It’s one we need to keep having, especially as their range expands!